An American economist, Nobel laureate, professor, public intellectual, and one of the 20th century’s most influential advocates for the free market. His ideas on monetarism, minimal government intervention, and individual liberty reshaped approaches to public policy, financial strategy, and the very understanding of capitalism. Read on at ichicago.net.

Biography

Milton Friedman was born on July 31, 1912, in Brooklyn to a family of Jewish immigrants. His parents ran a small business, but after his father passed away when Milton was just 15, the family faced financial hardship. Friedman grew up in the town of Rahway, New Jersey. Despite limited means, he was an exceptionally curious student with a special aptitude for mathematics and logic. In 1928, at only 16 years old, Milton enrolled at Rutgers University, pursuing a double major in mathematics and economics. He initially considered a career as an actuary, but two influential professors ignited his passion for the science of economics. At Rutgers, he was also introduced to the ideas of classical liberalism, which laid the foundation for his future worldview. After graduating with honors in 1932, he received a scholarship to continue his studies at the University of Chicago, one of the leading academic centers in the U.S.

From 1935 to 1937, Friedman worked for the National Resources Committee and in several federal agencies, focusing on projects related to tax assessment and price analysis. In 1946, he completed his doctoral dissertation at Columbia University.

The Chicago School of Economics

Milton Friedman became a key figure in the formation and development of the so-called Chicago School of economics—an intellectual hub born at the University of Chicago that became one of the most influential centers of economic thought in the 20th century. This movement was defined by its strong emphasis on market freedom, minimal government intervention, and the role of individual initiative as the engine of economic progress. Friedman was not only the movement’s leading theorist but also its chief popularizer and practitioner. He formulated the core economic principles that became the foundation of neoliberal doctrine—an ideology that champions free markets, private property, lower taxes, and deregulation.

Friedman believed the government’s role should be limited to ensuring law and order, protecting property, and creating the conditions for a competitive market. He argued against government interference in pricing, setting quotas, or regulating business. He fiercely criticized state monopolies, subsidies, taxation, and socialist tendencies, which he saw as threats to freedom and prosperity. Under the influence of the Chicago School’s ideas, particularly Friedman’s, the second half of the 20th century saw a massive shift in economic policy in many countries. These principles formed the basis for market liberalization reforms that profoundly impacted the economies of the U.S., the United Kingdom, and nations across Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Monetarism

Milton Friedman’s most famous theoretical contribution was the development of monetarism—a school of economic thought that challenged Keynesianism and changed the understanding of money’s role in the economy. Unlike the Keynesian approach, which emphasized fiscal policy and government spending to stimulate demand, Friedman’s monetarism focused on controlling the money supply as the decisive factor for macroeconomic stability.

The foundation of monetarist theory was the book “A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960” (1963), co-authored with economist Anna Schwartz. In this work, the authors used detailed empirical analysis to show that the Great Depression of the 1930s was not just a result of market failures but primarily a consequence of flawed monetary policy—specifically, a severe contraction of the money supply by the U.S. Federal Reserve. This was a revolutionary conclusion that posed a major challenge to the prevailing Keynesian consensus of the time. Friedman argued that excessive government intervention in the economy often does more harm than good. He believed the main task of central banks should be to ensure a stable and predictable growth in the money supply.

Political Views

Friedman’s influence was especially powerful on the administrations of Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and Margaret Thatcher in the U.K.—leaders who implemented a market-driven transformation of public finance and social policy. They introduced deregulation, privatization, tax cuts, and reduced government spending, rethinking the role of the state—all of which was closely tied to the ideas Friedman had been articulating since the 1950s and ’60s.

Friedman laid out his political philosophy in his foundational work, “Capitalism and Freedom” (1962). In it, he argued that economic freedom is a necessary condition for political freedom and that centralized planning is a danger to democracy. In Friedman’s view, the market is the only mechanism that ensures the efficient allocation of resources without coercion, and government intervention should be minimal, focused exclusively on protecting rights and freedoms.

In his public life, Friedman advocated for a number of proposals that were radical for their time but logically consistent with his philosophy. These included:

- A school voucher system, allowing parents to choose a private or public school for their child using a government subsidy. The idea was that competition among schools would improve the quality of education and reduce the influence of bureaucrats.

- Voluntary health insurance instead of a state-run medical system. Friedman believed that government regulation in healthcare leads to inflated prices, reduced efficiency, and limited innovation.

- Abolishing the military draft, which he called a form of “forced servitude.” Thanks in part to his efforts, the U.S. transitioned to an all-volunteer army in 1973, a major institutional shift during the Cold War.

- The decriminalization of drugs was another of his controversial ideas. He argued that the war on drugs, fought through criminal prohibitions, was ineffective, creating black markets and corruption, whereas legalization would allow for control and harm reduction.

Nobel Prize

In 1976, Milton Friedman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for “his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.” This recognition not only confirmed the significance of his academic research but also served as an official acknowledgment of monetarism as a full-fledged school of thought capable of challenging dominant theories.

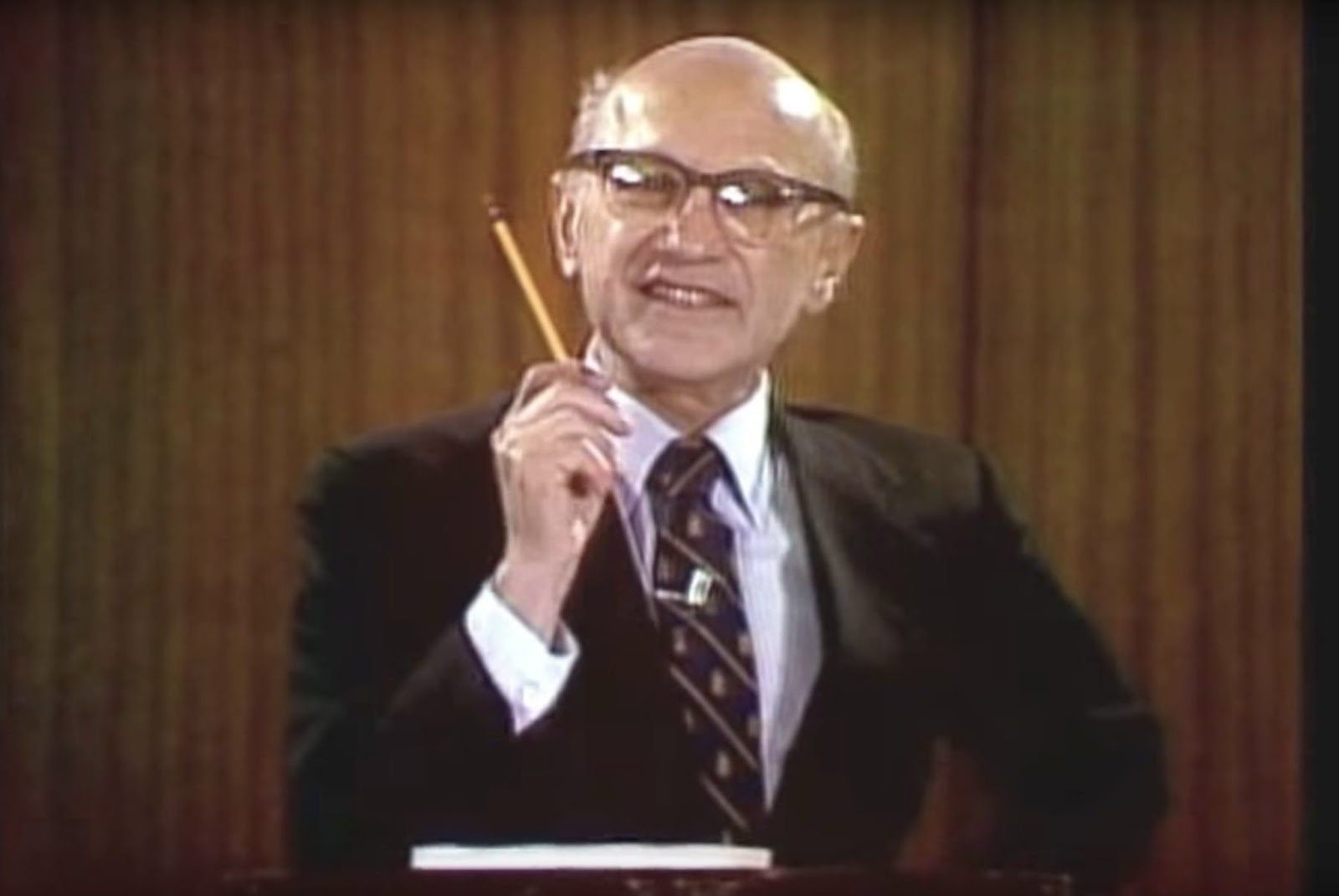

After retiring in 1977, Friedman did not disappear from the public sphere. On the contrary, he became an even more active public intellectual, regularly publishing in the press, appearing on television, writing books, giving interviews, and lecturing around the world. In 1980, he launched the television series “Free to Choose,” which became one of the most popular economic documentary series in history. In an accessible style, Friedman explained the principles of the free market, criticized government regulations, and argued for the benefits of individual freedom. The series was watched by millions of viewers in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Its effect was likened to an intellectual revolution in media, capable of changing society’s views on economic issues.

Milton Friedman died on November 16, 2006, at the age of 94 in California. His death was a loss for the global intellectual community, but his name lives on in textbooks, economic policy, and the ongoing debates about the future of the market and the state.