A theoretical physicist and one of the most prominent scientists of the 20th century, he made fundamental contributions to quantum theory, nuclear physics, and statistical mechanics. His work laid the groundwork for the development of atomic energy and modern particle physics. Read on at ichicago.net.

Biography

Enrico Fermi was born in Rome on September 29, 1901, to Alberto Fermi, a railroad administrator, and Ida de Gattis, a schoolteacher. His father worked for Italy’s Ministry of Communications, while his mother taught in an elementary school. The middle-class family placed a high value on education, which played a key role in shaping young Enrico’s scientific interests. From an early age, Fermi showed a remarkable aptitude for mathematics, mechanics, and logic, a brilliance that his teachers noticed even in elementary school.

The sudden death of his older brother, Giulio, in 1915 from complications after surgery was a profound shock for young Enrico. Deeply saddened by the loss, the 14-year-old Fermi immersed himself even further in his scientific pursuits. He found solace in books, independently studying the works of Newton, Maxwell’s “A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism,” and Einstein’s papers on the special theory of relativity. He took notes on his reading, solved complex problems, and sometimes derived equations on his own, all without any formal training in higher mathematics.

In 1918, Fermi passed the incredibly difficult entrance exam for the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, one of Italy’s most elite institutions, renowned for its focus on the natural sciences. At the university, he mastered classical physics, mathematics, and thermodynamics, but his true passion lay in the emerging theories of quantum mechanics and statistical physics. Fermi earned his doctorate in physics in 1922. Even then, his scientific style was marked by exceptional clarity, mathematical rigor, and the ability to bridge theory with experimentation. After graduation, Fermi secured a fellowship to study at the University of Göttingen in Germany.

Scientific Career

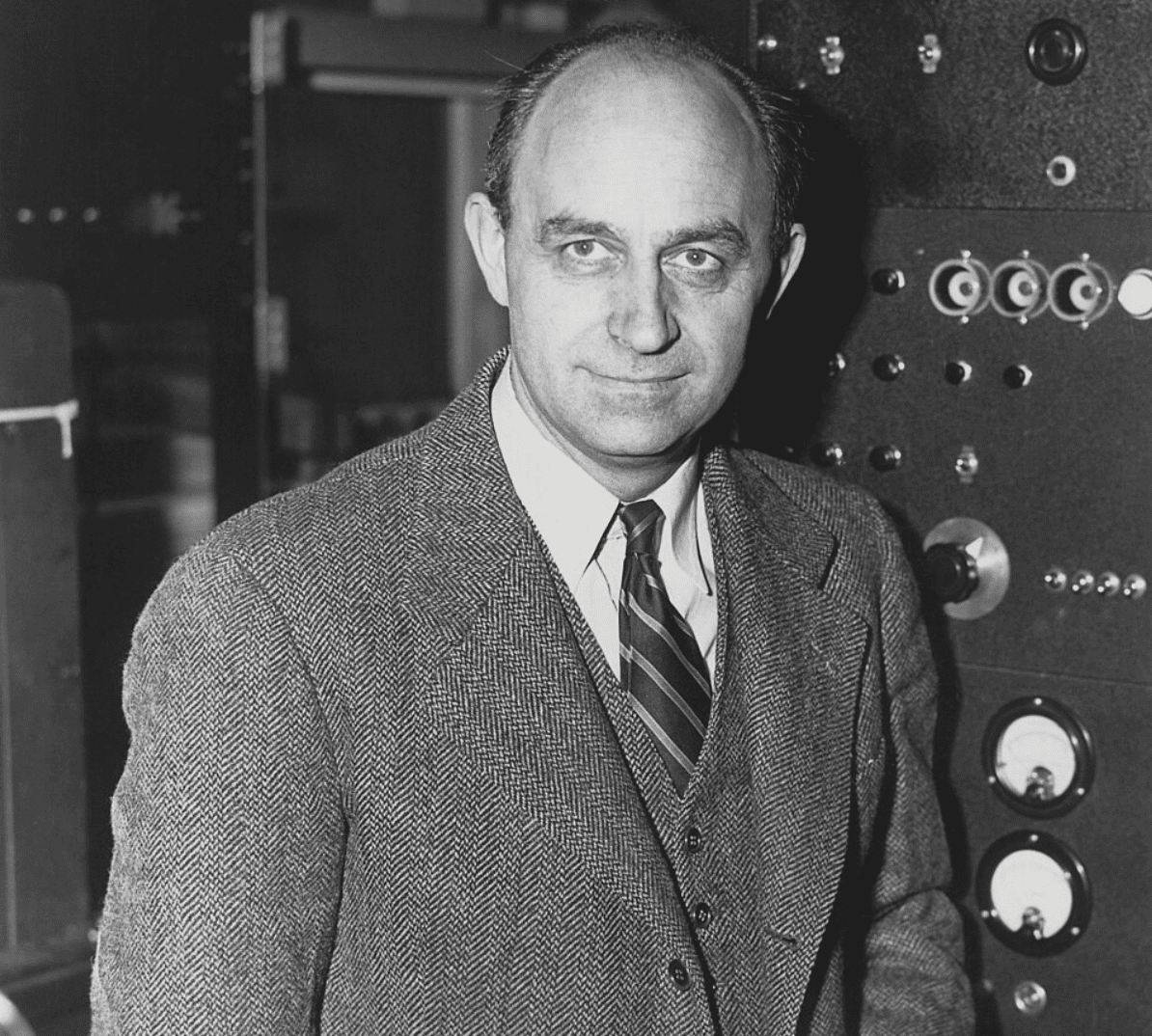

After fellowships in Germany and the Netherlands between 1923 and 1925, Enrico Fermi returned to Italy, where he quickly became a central figure in the scientific community. In 1926, he was appointed the first professor of theoretical physics at the Sapienza University of Rome. There, he assembled a team of brilliant young scientists that the scientific world would later call the “Fermi School.” Fermi published his work on the statistics of quantum particles with half-integer spin, formulating the principle that no two fermions can occupy the same quantum state. British physicist Paul Dirac independently reached the same conclusion around the same time. This model has since been known as Fermi-Dirac statistics. The breakthrough laid the foundation for the theory of electron gas, which later explained many properties of metals and became fundamental to the development of microelectronics.

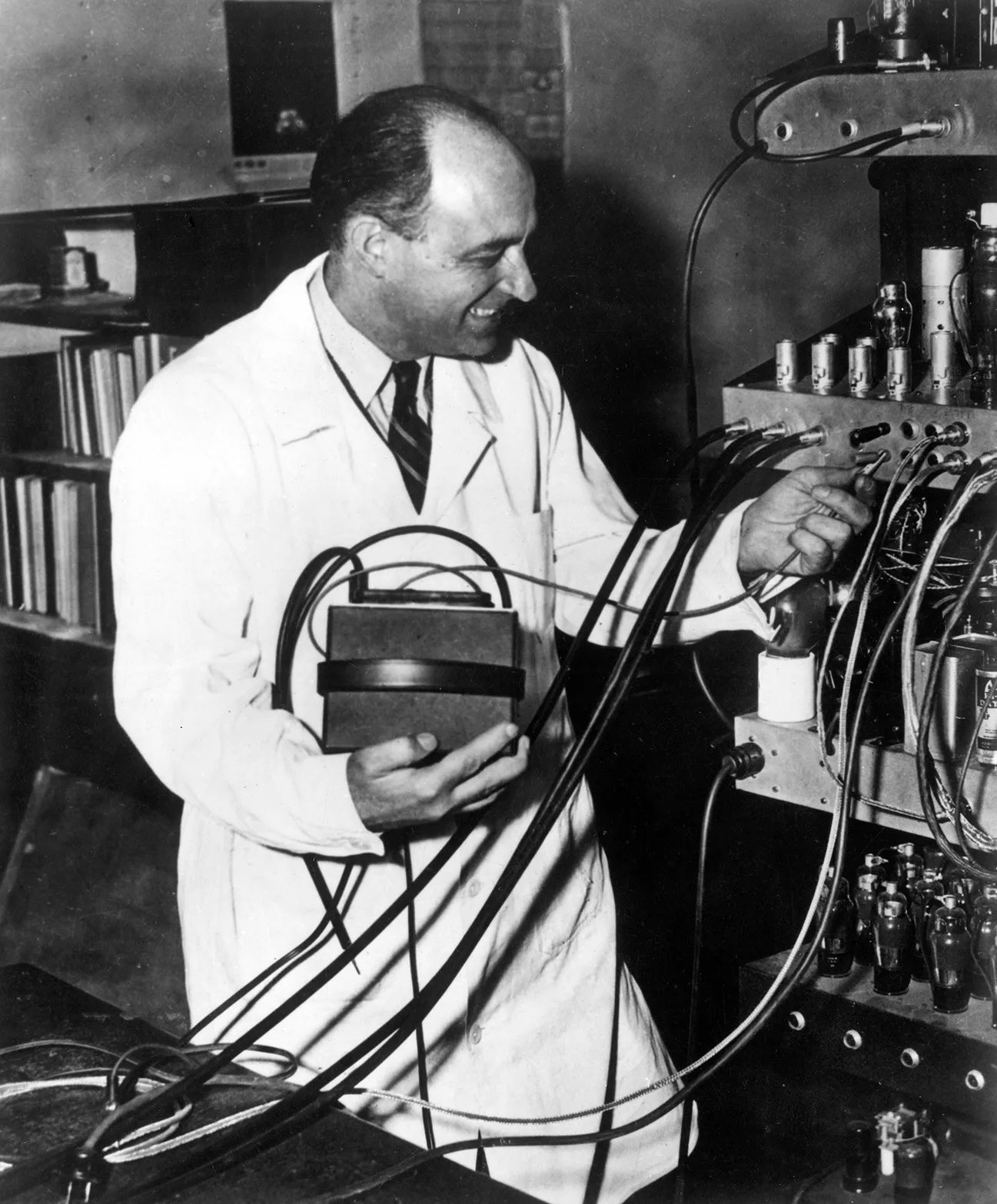

In the 1930s, Fermi shifted his focus from theoretical research to nuclear physics. In 1934, he conducted a series of experiments bombarding various chemical elements with neutrons. During these experiments, Fermi discovered that slow neutrons were far more likely to induce nuclear reactions than fast ones. This observation became a fundamental principle for all nuclear reactors, which still use moderated neutrons to efficiently control chain reactions. Based on this work, Fermi and his team created a series of new radioactive isotopes—a phenomenon later termed artificial radioactivity. For this revolutionary work, Enrico Fermi was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics “for his demonstrations of the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation, and for his related discovery of nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons.”

During an experiment bombarding uranium, Fermi almost accidentally achieved the first fission of an atomic nucleus—the very process that underlies nuclear energy and the atomic bomb. At the time, however, the physicist did not fully understand what had happened. Despite this initial misinterpretation, Fermi’s contribution to ushering in the atomic age was immense. His methodology set a new standard for modern physics.

Immigration to the U.S.

His decision to leave his homeland was driven not only by scientific opportunities but also by the political climate in Europe. Fermi had repeatedly expressed his opposition to fascism but avoided public confrontation with the regime. The scientific community in the United States welcomed one of the world’s leading physicists with open arms. Fermi accepted an offer from Columbia University in New York City, where he immediately joined research efforts in nuclear physics. Alongside his colleagues, he conducted a series of experiments that confirmed the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction. In 1939, Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein sent their famous letter to President Roosevelt, warning of the danger that the Nazis could create an atomic bomb, which prompted the U.S. to launch its own research. Fermi became one of the leading experts involved in this top-secret project.

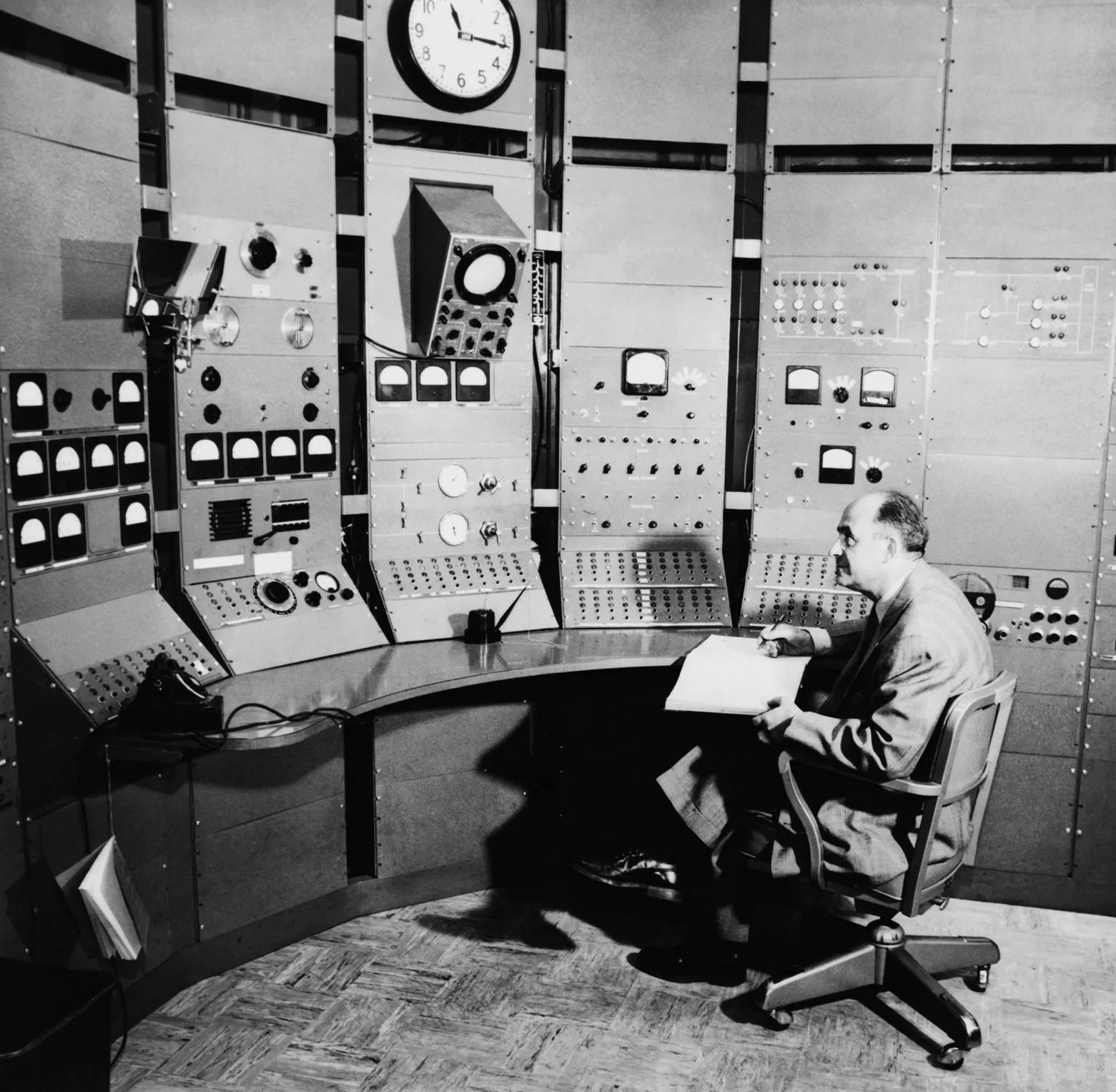

In December 1942, under Fermi’s leadership, a team of physicists built the world’s first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), located beneath the stands of the University of Chicago’s stadium. On December 2, 1942, this device achieved the first-ever controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, marking the dawn of the atomic age. Fermi personally handled the calculations for placing the graphite blocks and uranium slugs to ensure the reaction remained stable. Although the device was primitive by modern standards, it proved that nuclear energy could be controlled and therefore potentially used for both power generation and weaponry. Following the success of CP-1, Fermi became a key figure in the Manhattan Project—the top-secret U.S. government program to build an atomic bomb.

In 1944, he moved to Los Alamos, where, under the direction of Robert Oppenheimer, scientists from around the world worked on the weapon that would change the course of World War II. Fermi led theoretical and experimental groups, calculating explosion parameters and working on neutron physics and the energy balance of nuclear fission. He played a central role in ensuring that the calculations were not only accurate but also engineeringly feasible. After the war, Fermi advocated for openness in nuclear science and supported the peaceful use of atomic energy. He became one of the most influential scientific advisors to the U.S. government in the post-war years, particularly on the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

Post-War Activities

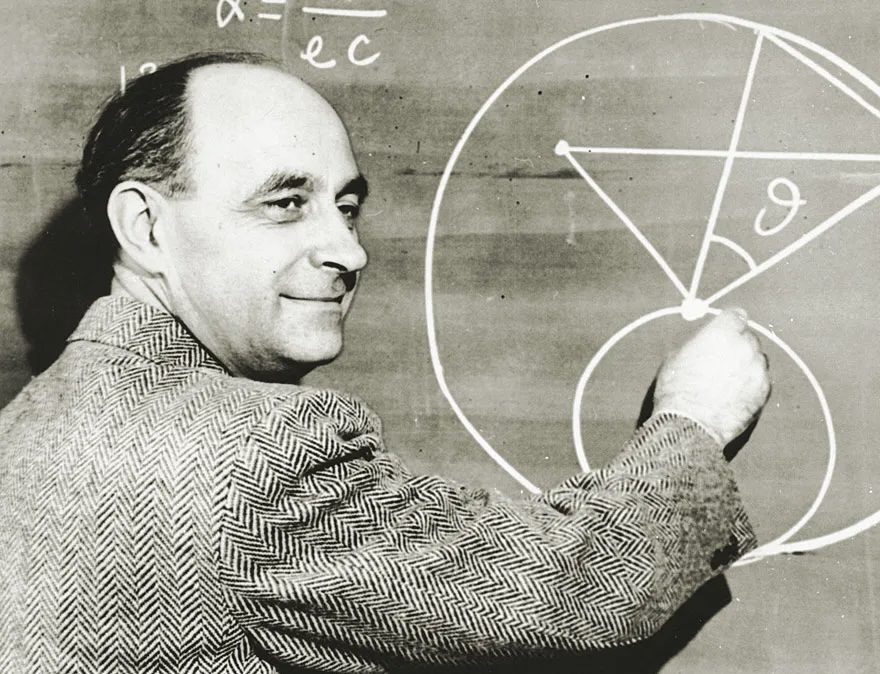

After World War II, Enrico Fermi focused on the peaceful development of nuclear energy and returned to academia. In 1945, he accepted a professorship in physics at the University of Chicago, where he remained for the rest of his life. His office and laboratory at the Institute for Nuclear Studies became a hub of modern science, shaping a new generation of physicists, with Fermi himself becoming one of the most influential mentors in the post-war scientific world. Fermi’s teaching skills were remarkable. He could explain complex concepts simply and logically, approaching his lectures with the same rigor and efficiency as his experiments. His lectures, particularly on quantum mechanics, field theory, and nuclear physics, became the basis for many textbooks. He was attentive to his students, encouraging not just knowledge but also critical thinking.

Fermi also continued to play a significant role in science policy. He served as an advisor to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, where he advocated for transparency in nuclear research and international control over nuclear weapons. Enrico Fermi died on November 28, 1954, from stomach cancer. Thanks to his multifaceted career, Fermi became a unique figure who combined the talents of a theorist, an experimentalist, a teacher, and a public advisor.