The Spanish flu epidemic left a negative impact on humanity. It claimed millions of lives. After devastating cities around the world, the Spanish flu swept through Chicago in the fall of 1918 and killed 8,510 people in just 8 weeks, according to ichicago.net.

The onset of the epidemic

The mass mobilization during World War I triggered the flu outbreak, which rapidly spread worldwide. A lot of young people left the country, contracted the disease and then brought it home.

The dangerous infectious disease was first recorded in the United States on March 11, 1918, at Fort Riley, Kansas. The military bases were the first to be hit by the disease. Then it spread to the civilians.

In Chicago, influenza first affected sailors at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. Officers quarantined the sick, but they still let visitors onto the base. As a result, the virus spread among the population.

Within one week, 522 patients had sought treatment at a Chicago hospital. On September 19, 1918, the Chicago Tribune reported that 1,000 people had mild flu symptoms. However, people did not believe this information and had their reasons for skepticism.

The disease from the Great Lakes swept throughout the suburbs of Chicago. The local government made tremendous efforts to stop it.

The fight against the flu

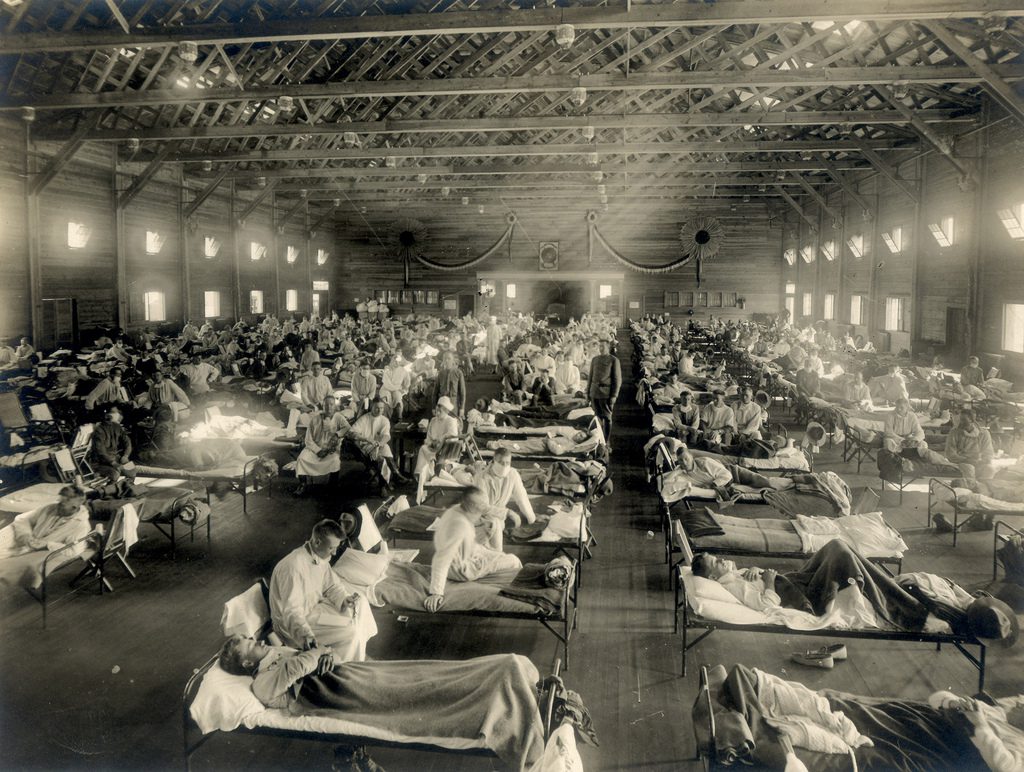

By the end of September, the city had turned into a real colony. Health officials ordered sick Chicagoans to observe quarantine. Although theaters, schools and churches were closed, public places remained open. In Lake Forest, police started patrolling the streets. Temporary hospitals were set up in country clubs. All efforts of the authorities did not pay off. Within 4 weeks, the virus reached the southern suburbs.

On September 21, 1918, the first case of death from influenza was recorded in Chicago.

Hundreds of new infection cases were recorded daily in early October. Chicago’s health commissioner, Dr. John Dill Robertson, said there’s no cause for alarm. Soon, he realized he was wrong.

The flu spared no one, taking the lives of both young and old people. Chicago faced a real tragedy, which prompted officials to take action. They immediately printed leaflets warning about the danger of coughing, sneezing and spitting in public venues.

Doctors recommended that people refrain from shaking hands when greeting each other. Signs were placed on buildings, saying “Kissing is forbidden.” All dirty handkerchiefs had to be boiled in water and soaked in disinfectant. Smoking in public places was strictly prohibited to reduce the amount of spitting and clean the air.

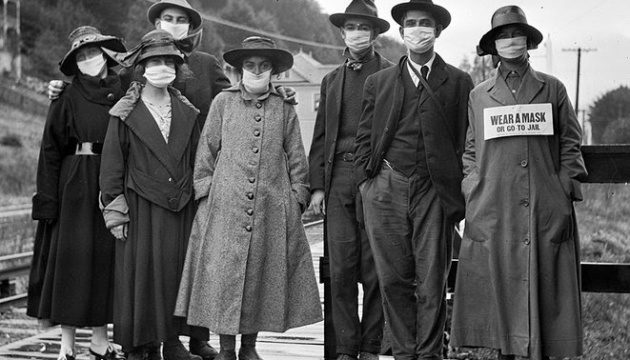

Commissioner Robertson suggested that people wear gauze facial masks to avoid microbes.

Soon, the police began arresting people who walked around with uncovered faces, sneezing and spitting. However, the police chief banned arrests and instructed officers to politely ask people to take protective measures.

Despite all these measures, the number of deaths in the city reached its peak by mid-October. The situation got so dire that all entertainment venues were shut down to prevent large gatherings and the spread of germs.

Sports events and gatherings were banned. Up to 10 people were allowed to attend funerals. Officials considered closing the city’s public schools but ultimately decided not to. Instead, teachers were instructed to keep windows open.

It was not until October 31 that the death toll reached 195 individuals. Then Robertson announced that establishments in the city would soon resume their operations. But the ban on smoking in public places would be permanent.

The Spanish flu was etched into the memory of Chicagoans forever.