19th-century Chicago was different from the modern one. At the time the city was founded on a swamp near Lake Michigan, no one could even think that soon it would suffer a real disaster, which would take thousands of lives. Learn more at ichicago.net.

Outbreaks of cholera

In the middle of the 19th century, the city suffered from a cholera epidemic that began due to unsanitary conditions. This infectious disease came up periodically. It attacked the city for the first time in 1852 and for the second time in 1854. During that period, the epidemic claimed 1,424 lives. The disease killed both young and old people within a few hours after the first symptoms. In 1854, 242 people died from diarrhea, one of the cholera manifestations. Unfortunately, at that time, no one knew exactly what caused the epidemic. However, doctors were more inclined to blame dirty and contaminated drinking water.

Besides cholera, other infectious diseases took people’s lives in the city. Thus, in the period from 1854 to 1860, 1,600 people died from dysentery and 1,200 from scarlet fever. In the period from 1858 to 1863, a smallpox epidemic raged in the city. As of 1864, it killed 283 people. Then the authorities began to think about how to solve the problem of dirt and waste and build a sewage system in the city.

In the summer of 1873, cholera returned again, killing 116 people. The Board of Health determined that death occurred within 11 hours of the first symptoms of the disease. The reports indicated that the infection hit hardest in areas with the worst sanitary conditions.

The fumes caused by rotting organic bodies (livestock) were also believed to spread infection. In the summer, the stench from the slaughterhouses engulfed Chicago, so it was impossible to breathe in the city.

In addition, the northern branch of the Chicago River remained stagnant accumulating sediments. In the hot months, it turned into a cesspool, poisoning the environment of northern areas.

The situation in Chicago stabilized and the death rate fell in 1873. It was facilitated by the laying of sewers, which effectively freed the city from sewage. In 1881, the Board of Health stated that Chicago had the third highest death rate in the world among cities with a population of over 500,000.

As medicine wasn’t yet developed enough, other infections began to attack Chicago and the authorities tried to fight them in every possible way.

Fighting diseases

At the end of 1870, the death rates from diphtheria and whooping cough increased dramatically. In 1877, scarlet fever accounted for more than 10% of deaths. These so-called “children’s diseases” were mortal and in the summer months, they were joined by others caused by spoiled food and contaminated water.

The most destructive epidemic in the history of the city was smallpox. In 1881, it took the lives of 1180 people and 1292 lives at the beginning of 1882.

Chicago’s population was growing too fast and so was the amount of waste. Every year from 1871 to 1881, thousands of horse carcasses and tens of thousands of stray dogs were removed from the city streets. 70 brigades tried to deal with the garbage on their own. However, the smell from cattle slaughter was still present and many wells were contaminated too.

The Board of Health was worried by the dangerously rapid increase in population. The situation in poor areas remained especially difficult. Thousands of one-family houses were overcrowded, with 5-10 people living in each room.

It also led to deaths from tuberculosis as well as infections associated with unsanitary conditions.

In 1891, 4,300 people died from bronchitis and pneumonia and 2,000 from typhoid fever. 10,000-12,000 5-year-old children were dying in Chicago annually. The authorities took some steps to stabilize the situation at the end of the 19th century.

Thus, the Metropolitan Sanitary District of Greater Chicago (now the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago) was created in late 1889. In addition, during that period, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was opened, forever changing the course of the river, diverting sewage and waste from Lake Michigan southwest to the Mississippi. Water chlorination began in the city in 1912. Tens of thousands of townspeople were vaccinated against diphtheria, which gradually eliminated the disease.

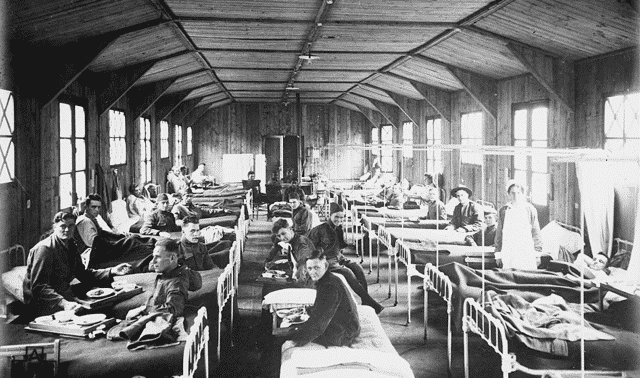

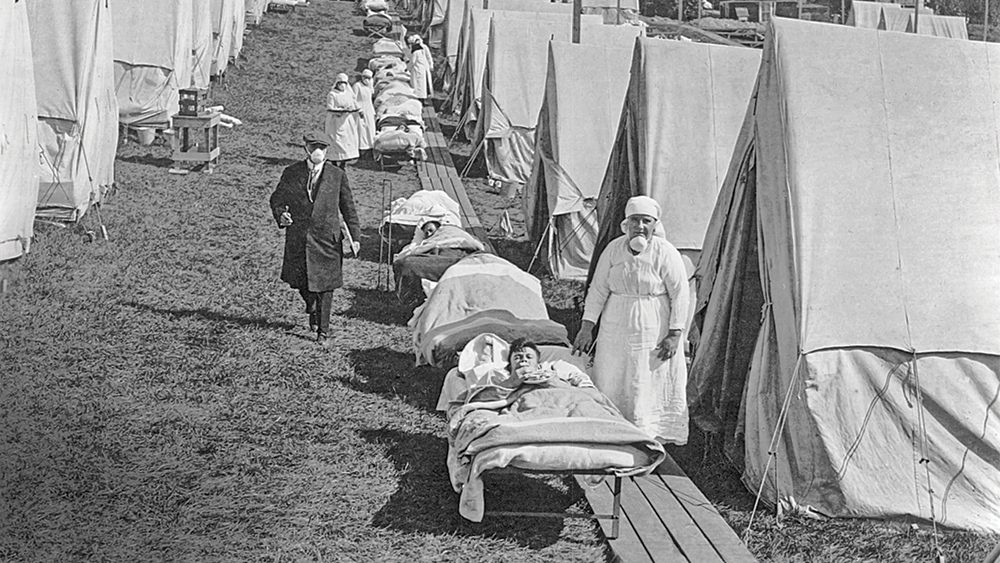

Epidemics of the 20th century

There were almost no catastrophic epidemics in the 20th century. In the period from 1918 to 1919, Chicago was attacked by the Spanish flu. In just one month, October 1918, about 20,000 people died from bronchitis and pneumonia, which arose as flu complications. However, the epidemic subsided soon.

The death rate from tuberculosis slowly decreased in 1920 and after the Second World War, the invention of antibiotics made the disease rare. However, until that time, poliomyelitis threatened to destroy the youth every year. Still, it also retreated, thanks to the Salk and Sabin vaccines invented in the 1950s.

During the 1960s and 1970s, some residents of Chicago suffered from sexually transmitted diseases. About 40,000 cases of gonorrhea were registered in the city annually, but they rarely led to a fatal outcome.

AIDS became the last epidemic in 20th-century Chicago. Since 1980, hundreds of people have died from this disease every year and in 1993 alone, their number was 1,000.