Richard Hunt’s name holds a special place in the global art pantheon of the 20th century. He became one of the most prominent sculptors, capable of transforming cold metal into a living organism. His work blends power and tenderness, industrial grit and natural flow, abstraction and surrealism. At the core of his creativity was always the concept of freedom—political, personal, and artistic. Read more on ichicago.

Biography

Richard Hunt was born in 1935 on the South Side of Chicago to an African American family. His artistic journey began very early: at age 14, he set up a small studio in his room to work with clay, later moving it to the basement of his father’s barbershop. A pivotal moment came in 1953 when Hunt visited the “Sculpture of the Twentieth Century” exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. There, he encountered the work of Spanish master Julio González, whose forged metal sculptures left a huge impression on the young artist.

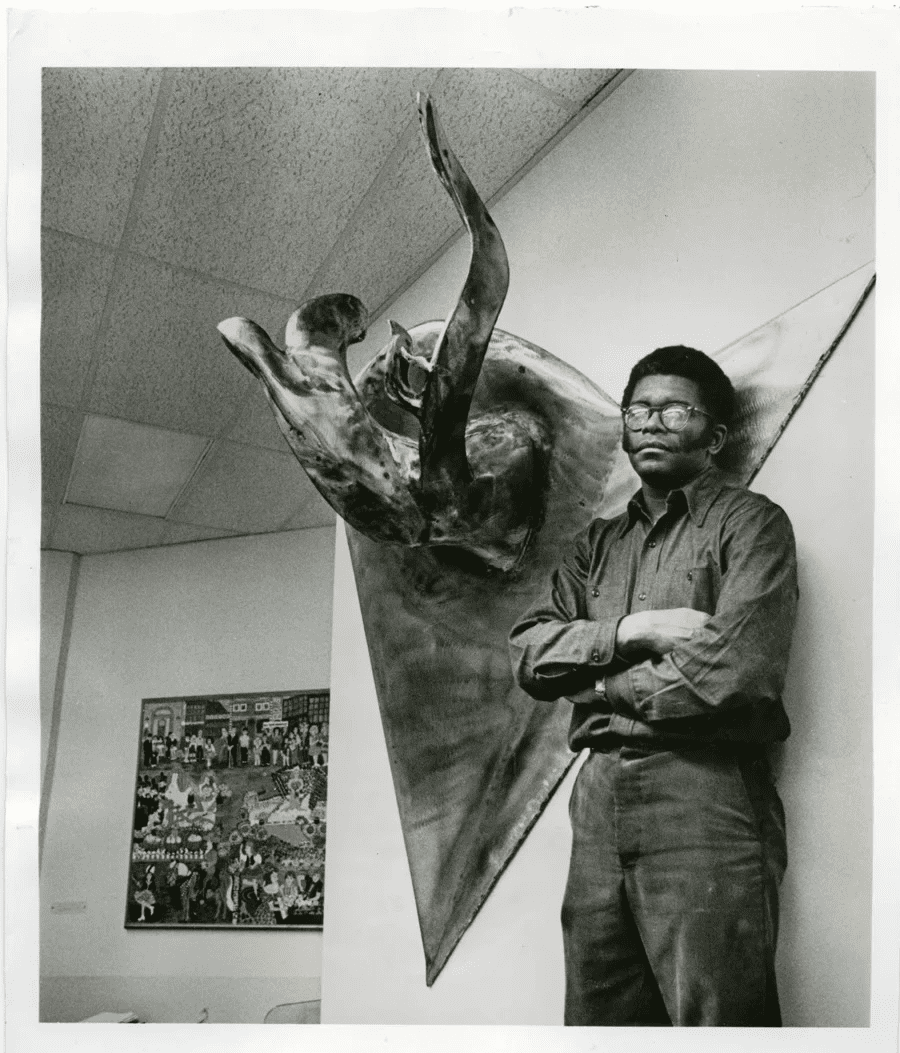

That same year, he enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. Influenced by González, he permanently abandoned soft materials and focused entirely on metal. Hunt taught himself soldering and welding, often using scrap metal from local junkyards. By 1955, he was already selling his works at Chicago art fairs.

After graduation, Richard received the James Nelson Raymond Foreign Travel Fellowship, which allowed him to embark on a journey across Europe. He crossed the Atlantic, visiting England and Paris. From Paris, Hunt rented a car and traveled through Spain and Italy. It was there that he mastered his first bronze casting at the renowned Marinelli foundry. This experience definitively convinced him that metal was the defining material of the twentieth century and laid the foundation for his subsequent work.

During his studies and travels, Hunt not only honed his technical skills but also gained cultural and artistic experience that shaped his views on materials, forms, and experimental sculptural work. The European trip became a key stage in forming Hunt’s artistic vision and his mastery of working with metal.

Creative Explorations

His interest in biology and natural processes played a major role in his art. Hunt saw metal as a medium capable of reflecting evolution, movement, and transformation. He often stated that he aimed to create forms that nature itself might generate if it had only fire and steel at its disposal.

In 1956, he created the sculpture Arachne, which was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. This marked the beginning of his national recognition. At the same time, Hunt was deeply affected by the Civil Rights Movement. The murder of Emmett Till, a young man from Chicago, became a symbol of the fight against racism and left a lasting imprint on his work. In 1971, he made history by becoming the first African American sculptor to have a retrospective at MoMA. The exhibition featured 55 sculptures, graphic works, and etchings.

Richard Hunt was an innovator who saw boundless possibilities in metal. He created what he called “drawings in space”—open sculptural forms that seemed to hover in the air. His works combined organic features with geometric ones, and the fluidity of line with the rigor of construction.

Beyond sculpture, he was actively involved in graphics and printmaking techniques. During his Ford Foundation Fellowship in 1965, he worked at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. There, he created multilayered, expressive compositions that would later become characteristic of his sculptures as well.

Public Art

Starting in the late 1960s, Hunt began creating large-scale public sculptures. He worked closely with engineers and fabricators, utilizing heavy industrial equipment. His pieces appeared in plazas, parks, and near museums.

Hunt’s first major public commission was the sculpture Play (1967–1969), created for the John J. Madden Health Center in Maywood, Illinois. Using steel, Hunt merged themes of mythology and current events: the sculpture draws upon the story of Diana and Actaeon from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, as well as the horrific footage of police persecuting Civil Rights activists in Birmingham in 1963. Play marked the start of his “second career”—working in the public realm.

Following this, in 1969, Hunt created the sculpture John Jones, dedicated to the first African American elected to a state office in Illinois. The sculpture blends geometric abstraction and figurative elements: blocks growing from Jones’s legs and shoulders symbolize the burdens and efforts he had to overcome. The sculpture is housed at the DuSable Black History Museum in Chicago.

Hunt dedicated a number of works to prominent African Americans. These include: I Have Been to the Mountain (1977) in Memphis, TN—a monument to Martin Luther King Jr., symbolizing mountain peaks as a metaphor for the struggle for equal rights; From the Ground Up (1989) honoring Mary McLeod Bethune; and The Light of Truth: Ida B. Wells National Monument (2021) in Chicago, which commemorates the journalist and human rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

Hunt frequently worked with metal, primarily Cor-Ten steel and bronze, creating forms that merged organic and industrial characteristics. Harlem Hybrid (1976) in New York stands apart from the minimalist trends of the era, emphasizing the synthesis of the natural and the mechanical. The sculpture Symbiosis (1978) on the Howard University campus features biomorphic elements resembling a head with appendages, underscoring the living nature of the metal. In works like Spirit of Freedom (1981), Hunt conveys the concept of freedom on two levels: as a symbol of the African American struggle for equal rights and as a metaphor for spiritual and creative liberty. From the Sea (1983) reflects the power of historical events and the triumph of good over evil through biblical motifs.

Many of Hunt’s sculptures are monumental in nature. Build-Grow (1986) in New York is reminiscent of the Tree of Life, while Eagle Columns (1989) in Chicago—standing 30 feet tall—honors Governor John Peter Altgeld and his fight for workers’ rights. Steel Garden (2013) symbolizes the fusion of industry and nature, and Swing Low (2016) at the National Museum of African American History and Culture pays tribute to African American spiritual culture.

Richard Hunt’s public sculptures do more than just decorate a space; they transmit powerful social and cultural messages. His work merges organic forms with industrial materials, artistic freedom with civic commitment. Through metal, Hunt tells a story of the struggle, heroism, and hope of the African American community.

Recognition and Legacy

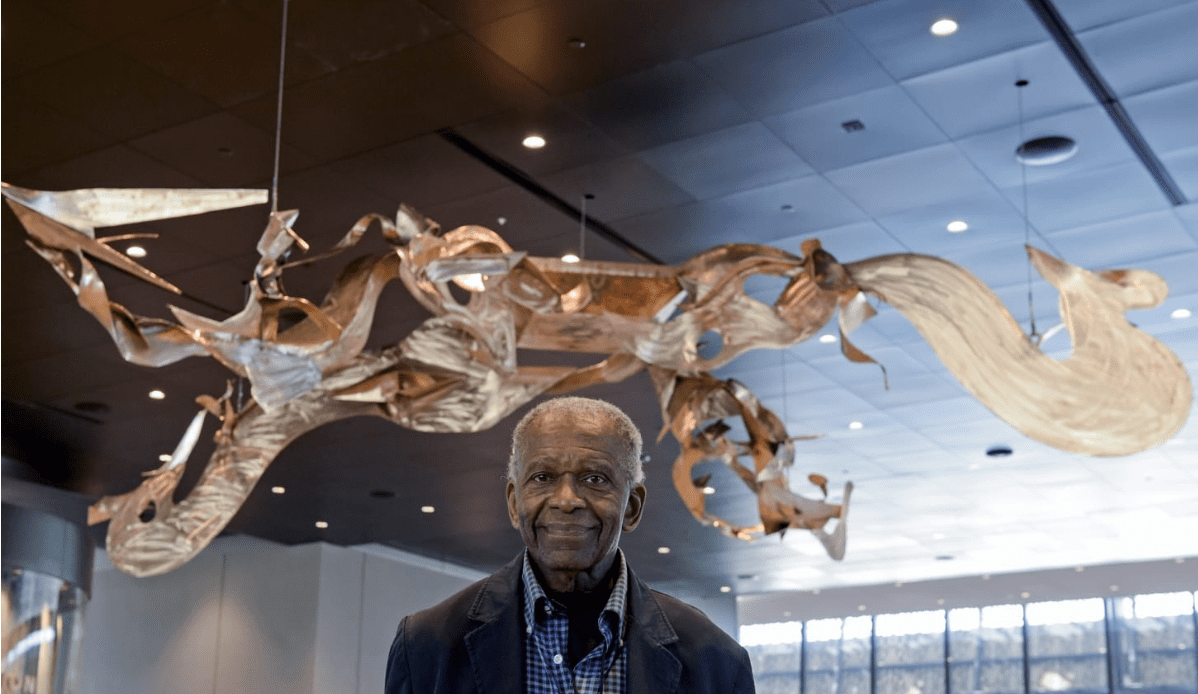

Over his 70-plus-year career, Hunt held more than 170 solo exhibitions and created over 160 public sculptures worldwide. His works are held in leading museums across the US and Europe, including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Smithsonian Institution museums.

The artist received numerous accolades, including a Guggenheim Fellowship (1962–1963), the International Sculpture Center’s Lifetime Achievement Award (2009), the Fifth Star Award from the City of Chicago (2014), and the Legends and Legacy Award from the Art Institute of Chicago (2022).

The life and work of Richard Hunt tell the story of an artist who felt matter by touch and knew how to bring cold metal to life. His art united nature and industry, mythology and modernity, struggle and harmony. Hunt, who lived his entire life in Chicago and brought the city worldwide renown, left behind a legacy that continues to inspire new generations.