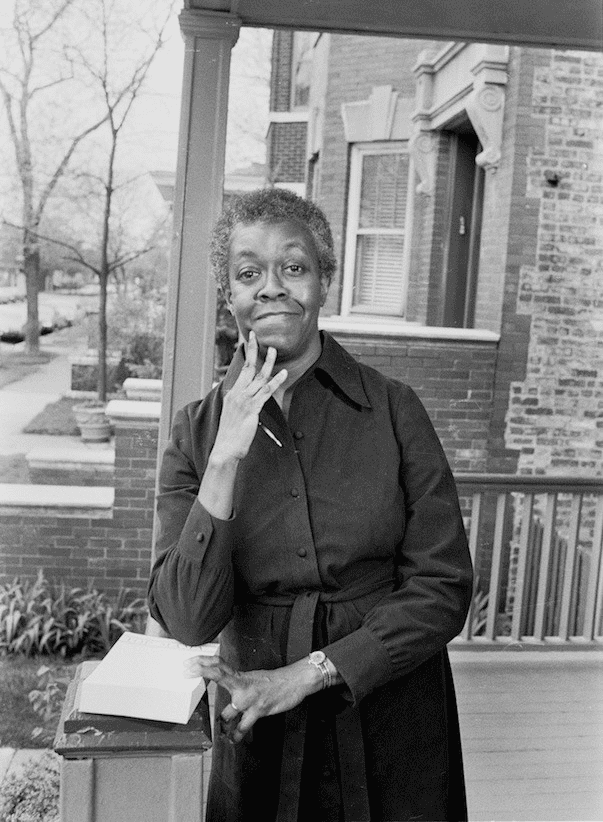

Her name is forever etched into the history of American literature. She was the first African-American to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and one of the writers who managed to transform poetry into the voice of an entire generation. Brooks didn’t just write about people the mainstream society was accustomed to overlooking; she forced readers to feel their pain, their dignity, and their yearning for freedom. She inspired deep thought and genuine societal change, leaving behind an unparalleled literary legacy. More on this topic is available at ichicago.net.

Biography

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was born on June 7, 1917, in Topeka, Kansas, but her life and legacy are overwhelmingly connected to Chicago. She was the first child of David Anderson Brooks and Keziah (Wims) Brooks. Her father was a janitor at a music company, though he had dreamed of becoming a doctor, and her mother was a schoolteacher and a professional pianist. It was her mother who first recognized and supported her daughter’s talent. Family history holds a story that Gwendolyn’s paternal grandfather escaped slavery to fight for the Union during the American Civil War. When Brooks was an infant, her family moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration of African-Americans from the South. From then on, she called Chicago her “headquarters,” as she later put it. In a 1994 interview, the poet emphasized that Chicago shaped her as an artist, saying that life in the city gave her countless images, narratives, and characters that found their way into her poetry.

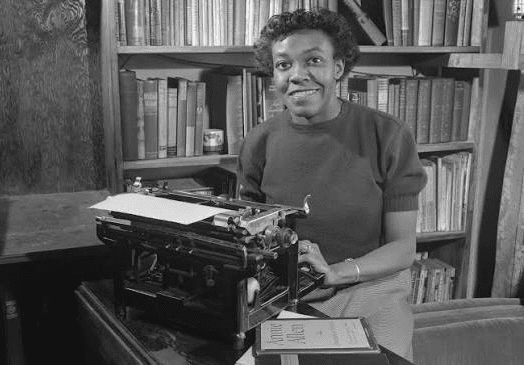

The future writer attended several Chicago schools—first Forestville Elementary, then the prestigious but predominantly white Hyde Park High School, followed by Wendell Phillips High School, and finally, the integrated Englewood High School. This constant transition between environments, where racial injustice was palpable, hardened her worldview. Biographer Kenny Jackson Williams noted that it was during this time that Brooks realized the depth of prejudice, which characterized not only specific institutions but American society as a whole. She began writing very early; her first poem was published in American Childhood magazine when she was just 13. Before graduating high school in 1935, she was regularly published in the prominent African-American newspaper, the Chicago Defender. After two years of study at Wilson Junior College, Gwendolyn worked as a typist while continuing to develop her literary career.

Poetry Collections

In 1945, her first collection of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, was published and highly praised by the writer Richard Wright. In these verses, Brooks depicted the lives of African-Americans in the Bronzeville neighborhood without romanticizing, truthfully reflecting their tragedies, joys, and the small details of their daily existence. Critics noted her ability to capture the drama of “small fates” and deeply explore the issue of racial prejudice.

The true breakthrough came in 1949 with the publication of her second collection, Annie Allen. In it, the poet tracked the journey of a young Black girl into adulthood amidst inequality. This book earned her the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, making her the first African-American to receive such an honor.

In 1953, Brooks’s only prose work, the novella Maud Martha, composed of 34 vignettes, was released. It explored the complex inner world of a Black woman who faces not only racism from white people but also prejudice within her own community. Critics emphasized that the work is simultaneously a story of a humble heroine’s triumph and a profound critique of social injustice.

The 1960s marked a new phase in the poet’s life. In 1967, at the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University, she met representatives of the Black Arts Movement, which significantly influenced her subsequent work. She began collaborating more with independent publishers and mentored young poets from Chicago’s troubled neighborhoods, including former gang members. In 1968, her poem In the Mecca was published, earning her a nomination for the National Book Award.

Brooks remained highly active in the following decades. She published new collections, including Primer for Blacks (1980), To Disembark (1981), Blacks (1987), and Children Coming Home (1991). She also penned two volumes of memoirs, Report from Part One (1972) and Report from Part Two (1995), combining autobiographical reflections with essays and interviews.

Acclaim and Legacy

Gwendolyn Brooks’s work was widely acclaimed during her lifetime and has left a powerful cultural legacy. In 1946, she was a Guggenheim Fellow in Poetry, and just three years later, she received the Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize from Poetry magazine. The collection Annie Allen brought her the Pulitzer Prize in 1950. In 1968, she was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois, a title she held until her death.

The list of her awards only expanded from there: the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award (1969), membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1976), the Langston Hughes Medal (1979), appointment as Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress (1985), and numerous honorary degrees from leading literary organizations. In 1995, Brooks received the National Medal of Arts, and in 1997, the Order of Lincoln, Illinois’s highest honor.

Her memory lives on in the names of institutions and cultural centers. Schools, university literature centers, a library in Springfield, a park in Chicago, and cultural programs bear her name. In 2010, she was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, and in 2012, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp featuring her image.

The centennial of her birth in 2017 was marked by large-scale tributes: Chicago hosted poetry readings, discussions, and exhibitions dedicated to her legacy. In 2018, the Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville sculpture was unveiled in the park named after her. Through numerous honors, landmarks, and cultural initiatives, Gwendolyn Brooks’s name continues to inspire new generations of writers and readers. Her life exemplifies how a personal voice can transform into the symbol of an entire era.

Teaching and Personal Life

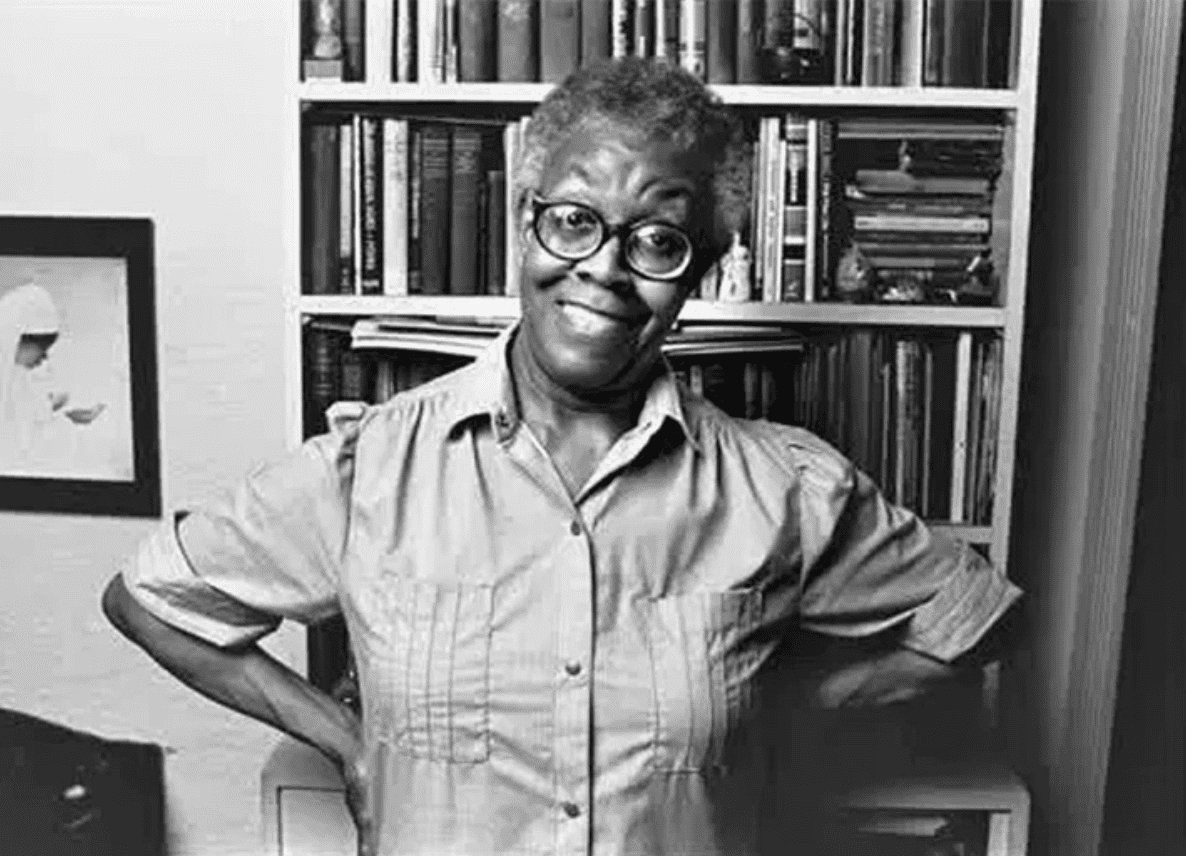

A significant part of her life was dedicated to teaching. She led creative writing and literature courses at the University of Chicago, Columbia College, Northeastern Illinois University, City College of New York, and other educational institutions. In her role as a mentor, she supported a whole generation of young authors, helping them discover the power of their own voices.

Gwendolyn Brooks was a wife and mother. In 1939, she married Henry Lowington Blakely Jr. The couple had two children—a son, Henry III, and a daughter, Nora, who later donated her mother’s archives to university libraries.

The poet remained devoted to Chicago until her final days. She passed away on December 3, 2000, at her home. Her death was a loss for all of American literature, but Gwendolyn Brooks’s legacy continues to thrive in her poems, which reflect the dignity, pain, and hopes of generations of African-Americans. Her work is a chronicle of the lives of ordinary people whose stories were often ignored by “high” literature. Thanks to Brooks, these voices resonated at full strength, and she herself became a symbol not only of Chicago but of a whole cultural resistance in America.